Next time I publish notes on a book, I’ll be more careful to frame why it’s actually interesting to me. It’s been a pretty dry month for this blog. The notes took a particularly long time because I lost my little offline copy of quote transcriptions, and a significant amount of willpower with it.

A few more posts coming this week.

—

1. Why Institutions Fail to Adapt

1.1 Intellectual Rigidity: Humans “follow institutional rules for reasons that are not entirely rational”- and I’m sure that you’ve thought of several reasons before even finishing this sentence.

1.2 Elite Capture: Political incumbents vote for stasis.”Political institutions develop as new social groups emerge and challenge the existing equilibrium. If successful institutional development occurs, the rules of the system change and the former outsiders become insiders.” Modern states are vulnerable to “insider capture”. Even in democracy, elite insiders generally have better resources and information to protect themselves with.

2. Unique American Flavors of Decay

The decay of (say) American political institutions is not the same as societal/civilizational decline. America has never really rested on the quality of its government, which has generally been pretty low.

Political decay in this instance simply means that many specific American political institutions have become dysfunctional, and that a combination of intellectual rigidity and the power of entrenched political actors, growing over time, is preventing the country from reforming them. Institutional reform is an extremely difficult thing to bring about, and there is no guarantee that it will be accomplished without a major disruption of the political order.

19th century America was referred to by Stephen Skowronek as a “state of courts and parties”, where traditional executive branch activity was reallocated to judges and representatives. An executive bureaucracy developed late (and sloppily) in the US system. The scope of American government has increased in the past century, but its strength (quality) arguably did not. What’s more, the traditional constraining institutions, Rule of Law (courts) and Accountability (parties), have in recent decades been used as alternative tools of government expansion. Even heroic episodes of American history (e.g. the Civil Rights movement of the ’60’s) moved through channels that are rare outside of the United States system. In other liberal democracies, public pressure led directly to state action, instead of motivating private entities to engage in court battles to change policy. America’s court systems also resolve situations that in Sweden or Japan would be resolved by consultations within state bureaucracy. “Uncertainty, procedural complexity, redundancy, lack of finality, and high transaction costs” result.

Fukuyama argues (against virtually no one) that “judicialization of administration and the spread of special interest-group influence [tends] to undermine people’s trust in government.”

The problems of American government arise, then, because there is an imbalance between the strength and competence of the state on the one hand, and the institutions that were originally designed to constrain the state on the other. There is, in short, too much law and too much “democracy” relative to American state capacity.

Criminalized bribery is narrowly defined in American law as a transaction in which a politician and a private party explicitly agree upon a specific quid pro quo exchange. What is not covered by the law is what biologists call reciprocal altruism, or what an anthropologist might label a gift exchange.

—

3. Private Organizations / Interest Groups

3.1 Mancur Olsen’s The Rise and Decline of Nations argued that democracies tended to accumulate rent-seeking interest groups in time of peace. The general public could not act collectively to consistently defend against this problem. Only a large shock like war or revolution could root out the rent-seekers.

3.2 Alex de Tocqueville argued in Democracy in America that private organizations were “schools for democracy”, and a vibrant and important part of American civil society. It is only through individuals voluntarily associating that they could become strong enough to fend of tyrannical government.

3.3 James Madison once argued that diversity of interests would keep one group from asserting definitive dominance. Like many ideas, this one resurged much later: mid-20th century ‘pluralist’ political theory asserted that the “public interest” was the result of the interacting interest groups in the same way that competition in the free market would create public benefit out of narrower self-interest.

How, then, do we reconcile these diametrically opposed narratives- that interest groups are corrupting democracy and harming economic growth, and that they are necessary conditions for a healthy democracy?

The “easy” answer that Fukuyama first suggests is that perhaps the good ‘uns are ruled by Hirschman’s “passions”, and the bad ‘uns by his “interests”. This is an unsatisfying answer, though, because a group’s motive being self-interested does not disqualify them from having a voice in our society, and a group claiming to act or speak for the public interest may not be doing so. Also, clearly, a group will likely have a mix of self-interest and public-mindedness. No easy answers.

4. Trust and Government

Distrust in government is a self-fulfilling prophecy in many respects. I won’t dwell on this because it seems obvious. Politics and ideas are the two obstacles standing in the way of reversing these tendencies of decay:

- Politically, it tends to take a great shock to catalyze the birth of a reform coalition, like the post-Garfield assassination outrage that finally rolled back the American spoils system, the Great Depression, or the world wars. Leadership and a clear agenda are necessary but not inevitable.

- Cognitively, American habits are to expand democratic participation and transparency to remedy government dysfunction.Well-organized and funded activists, however, benefit disproportionately from these efforts. It might not be popular to advocate “less participation and transparency”, though.

Many of these problems could be solved if the United States moved to a more unified parliamentary system of government, but so radical a change in the country’s institutional structure is inconceivable. Americans regard their Constitution as a quasi-religious document, so getting them to rethink its most basic tenets would be an uphill struggle. I think that any realistic reform program would try to trim veto points or insert parliamentary-style mechanisms to promote stronger hierarchical authority within the existing system of separated powers.

Note to consider: “The Confucians were right in arguing that no set of rules can ever be adequate to produce good results in all cases.” The intangible factor to grease the political system is trust. The high equilibrium to strive for is one in which trust in government begets effective government which reinforces that trust. The low-level equilibrium comes more easily to mind: low-quality government begets distrustful citizens, who then withhold compliance and resources that the government would need to be effective. Without authority, “government turns to coercion to achieve compliance”.

It is [possible] that as citizen’s expectations and demands multiply, all governments are headed toward the low-level trap.

It seems easy to fall out of the high-equilibrium loop down to the low. Moving up would involve building government capacity and autonomy.

5. Political Order and Political Decay

5.1 Political Development is an Evolutionary Process:

Political development is similar to biological evolution in a number of respects. The latter is based on the interaction of two principles, variation and selection. So too in politics: there is a variation in the nature of political institutions; as a result of competition and interaction with the physical environment, certain institutions survive over time while others prove inadequate. And just as certain species turn out to be maladapted when their environments change, so too political decay occurs when institutions prove unable to adapt.

However, a key difference is that human beings “exercise some* degree of agency over the design of their institutions” whereas biological evolution is random.

Fukuyama identifies five major transitions in political institutions that have taken place independently across humanity. None of these movements are universal to all humans everywhere, but they are very large and consistent transitions:

- From band-level to tribal-level societies [i.e. starting from the dynamics that we are born with, reciprocal altruism and kin selection, we were band-based until the idea of an expanded concept of family was introduced through ancestor/descendant worship and larger tribes were capable of coalescing.]

- From tribal-level societies to states [i.e. agriculture and new non-kin, hierarchical forms of organization allowing for large-scale agrarian empires, for example.]

- From Patrimonial to Modern States [i.e. The birth of modern bureaucracy, the concept of public/private spheres, and the decay of the idea of a state being owned by its Monarch.]

- The development of independent legal systems [i.e. the Rule of Law, a concept that can dictate even the legitimacy of the state’s actions]

- The emergence of formal institutions of accountability [i.e. democracy and other forms of feedback between government and “the public”.]

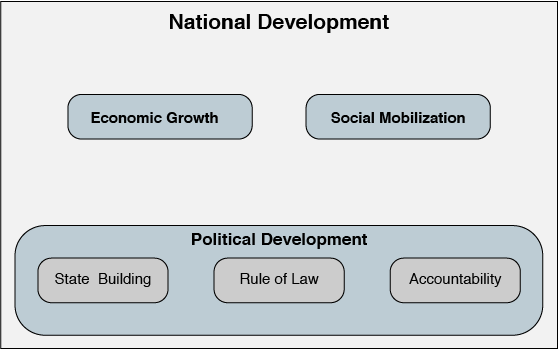

5.2 Briefly Reviewing National Development:

This model of development shows the “three central political institutions […] come under pressure as rapid social mobilization fosters demands for political participation. This is the critical juncture at which political institutions of the agrarian order either adapt to accommodate demands for participation or else they decay.” [this would be the scenario where Economic Growth -> Social Mobilization -> Democracy.] This is the classic path towards modernization for Western Europe, North America, and East Asia, but it is not the only path. Social Mobilization without sustained economic growth yields what Fukuyama dubs “Modernization Without Development” [Social Mobilization -> Democracy, which hinders The State.] Instead of industrial development pulling peasants into cities for employment, rural poverty pushes them, and they bring old values and forms of organization with them. This is the path that Greece and Southern Italy have followed, and many developing countries are on this path.

Although Fukuyama models political development as a closed system, obviously it cannot be. Even in the absence of conquest and coercion, international-level concerns influence political development, especially concerning ideas about legitimacy.

Does the existence of political decay in modern democracies mean that the overall model of a regime balanced among state, law, and accountability is somehow fatally flawed? This is definitely not my conclusion: all societies, authoritarian and democratic, are subject to decay over time. The real issue is their ability to adapt and eventually fix themselves. I do not believe that there is a systemic “crisis of governability” among established democracies.

Oh, whew.