Originally, this blog was a sort of challenge to write continuously for a little while. I’ve sort of got the hang of it, but I wanted to focus some effort on other things, so I am reducing my output after next week’s pretty sizable posts. I figured it wasn’t cheating by my own lights, since I only committed myself originally to one post per week, anyway.

Next week I’m back at more sprawling, loosely connected posts- about analogical reasoning, “unthinkable thoughts”, weird fiction, and finally a bit about videogames and game development.

This post is about some simple ideas that were missing (as formal ideas, anyway) from my toolkit until relatively recently.

I attended a lecture by Jon Kolko ~3 years ago. It was called “Right Time, Right Place: Applying the discipline of design to the emerging problems facing society“, and it re-framed the role of design as I saw it at the time. Kolko is interested in social entrepreneurship and using the lens of design to think rigorously about how to approach “wicked problems”. His presentations are accessible on his site, and his latest book is available to read online.

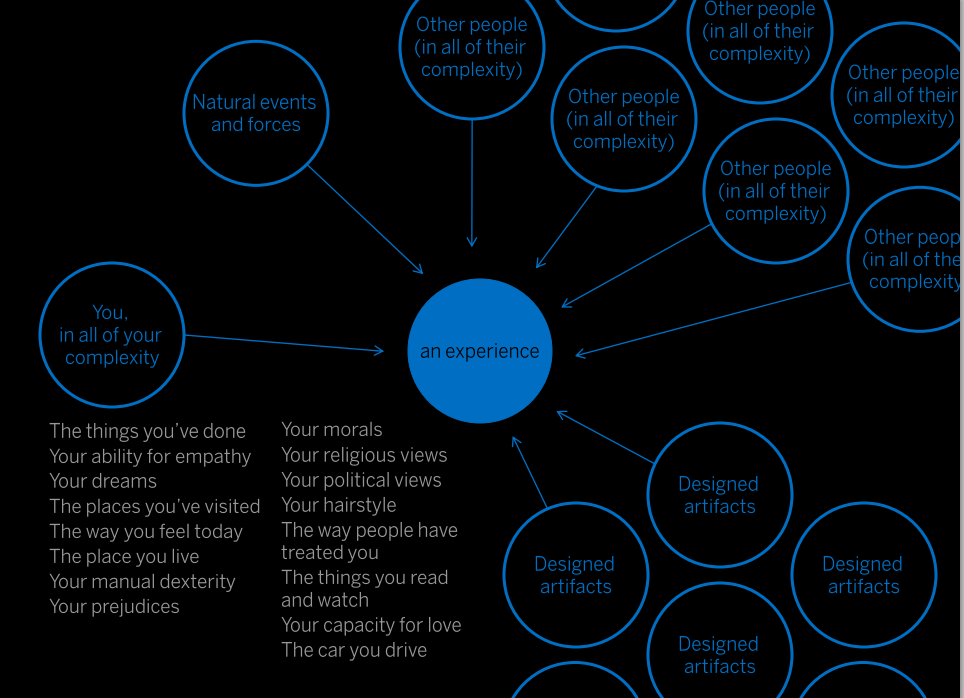

Kolko’s definition of design is “the creation of a representational dialogue between people and products, services and systems encountered in everyday human experience.” [Note: As I see it, “representational dialogue” is a superset of “procedural rhetoric.”] Design is an abductive problem-solving process that (usually) has a formal manifestation. This is a story about a party that I’ve been very late to.

Methods of Reasoning

Deductive reasoning is the simplest and most certain form of reasoning. Chris is a dog. All dogs can bark. Therefore, Chris can bark. In deductive reasoning, the conclusion is always true when the premises are true. We have a language for describing deductive reasoning. If it’s good reasoning, the argument is valid (that is, we must say the conclusion is right if the premises are true); if the reasoning is good and the premises are in fact, true, then we can go farther and say that the argument is sound.

Inductive reasoning takes an ounce of experience. Every dog I’ve seen has a tail. Therefore, the next dog that I see will have a tail. As this example illustrates, inductive reasoning gives us a likelihood that the conclusion will be true. But inductive reasoning can’t be valid or sound, because we can’t make any guarantees even if we know the premises are true. It is conceivable that every dog I’ve seen has a tail but the next one won’t. Instead the language we use for inductive reasoning is how weak or strong it is. Instead of looking at binary true/false like in deductive reasoning, we have to look at likelihoods.

Abductive reasoning, unlike the other two, was never defined to me until college. When it rains, the grass gets wet. The grass is wet, so it may have rained… (this is a fallacy if taken as absolute and deductive). Abductive reasoning involves working out the best explanations given the circumstances, and given the experiences of the reasoner. It is an analogical process. Deductive reasoning can be measured by validity and soundness; inductive reasoning can be measured by strength/likelihood; abductive reasoning is unique because two different reasoners can abduce two different answers. Abduction is the act of sense-making and the process of serendipity. It’s the birthplace of the hypothesis. It’s also where contextual research happens. The same year I learned about abduction, I also took a class on Pragmatism, focusing mainly on the work of C.S. Peirce, William James, and John Dewey. Peirce is responsible for formalizing abduction into modern logic. It was a strange year for me.

My Own Introduction to Design Thinking

When I started going to Carnegie Mellon, I was interested in using interfaces to attempt to address wicked problems (I still am). I intended to get a double major in Information Systems (to build interfaces) and Decision Science (to study behavior). But one thing that immediately surprised me was how while social sciences do attempt to grapple with difficult problems, there was also a class of people who called themselves “designers” who didn’t do what I saw at the time as trivial ‘beautifying’ work- they were out in the field, collecting data, building usable, useful things, iterating on them, and making a quantifiable difference in some very difficult, complex spaces. I didn’t want to call these people “designers”, really, because to my younger self design was a luxury to lather onto products for rich people. Design was the iPhone, in my mind, not the Saturn V (that was helpfully labeled as something different, “engineering”). It’s hard to even explain my old attitude without making my previous self into a bit of a strawman. But, as a person who did not naturally see the world of color palettes and fonts, this new method of understanding (and the idea that it was formalized, and not just “woo woo”) was a revelation to me. People were finding ways to use empathetic, abductive reasoning to solve problems that they didn’t necessarily understand axiomatically. They attempted to understand the problems behaviorally and they tried and failed and took notes and tried again. They mapped out how people were behaving, envisioned a way that could improve that process, and built new options for people. I thought that majoring in Human-Computer Interaction (instead of Information Systems) and Decision Science was a better course of action for me, because HCI training involved a lot of modelling, contextual research, and methods of empathizing with the user that were absent from the focus of my other, social-science major (while Decision Science was more formal, and gave me research experience and a vocabulary for behavior).

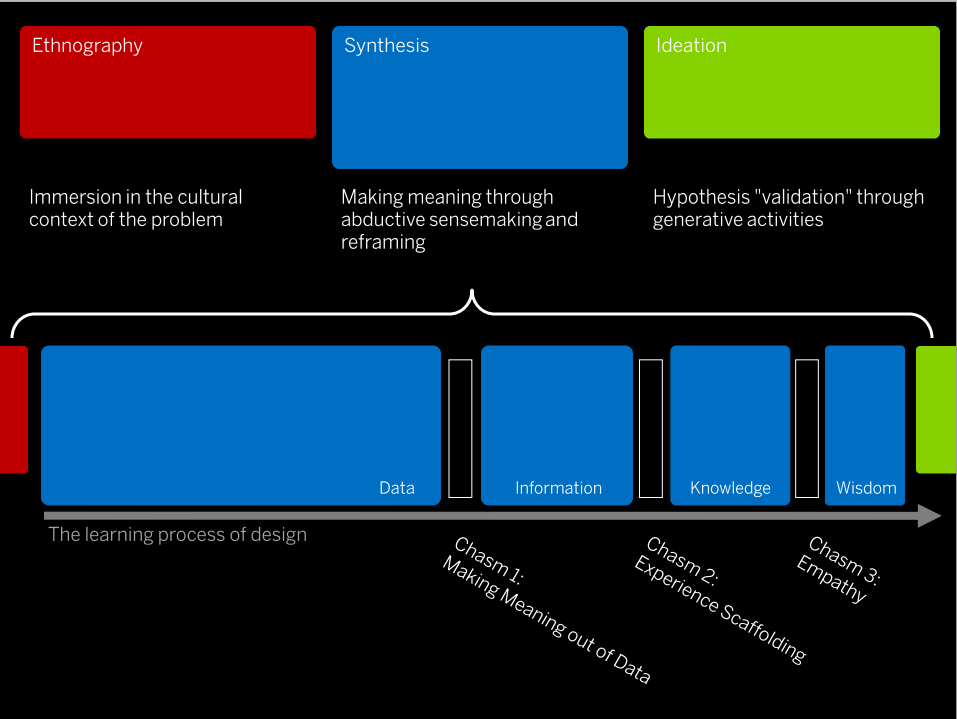

Design synthesis is the “secret sauce” used when engaging with large-scale complex problems and social entrepreneurship.

Design synthesis is an abductive sensemaking process of manipulating, organizing, pruning and framing data in an effort to produce information and knowledge.

-Jon Kolko, “Right Time, Right Place: Applying the discipline of design to the emerging problems facing society“

In the HCI program, I felt out of place often, surrounded usually by other students with beautiful portfolios and backgrounds in making pleasurable apps. At the time, that wasn’t where I was coming from or what I was really interested in. I wanted to design behaviors, not posters or screens. While most of the non-methods classes were about screens (which I had to learn to appreciate), many of the professors in HCI that I met with were social scientists that I tried to learn from: folks in UbiComp, and studying social networks. My interest in game development is partially the fun of making something, but I also got involved in game development because games were an interesting medium to study behavior through: I used games research to collect an undergraduate research fellowship, I spent a summer working on a DARPA-funded learning game, and I read about games studies and games-as-rhetoric, persuasive games and learning games, and gamification. In the same way that I learned to stop trivializing design, I started to see games as potentially extremely potent tools. I was never interested in working for an entertainment company, and I have always outright disliked gaming culture to be honest. My relationship to game development has always been very strange and difficult for me to easily define. I usually opt to just call it a hobby but I’ve suppose I actually see it as a bit more than that.